Governance Structure for Clinical Decision Support Systems Operating Within the European Single Market

Published:

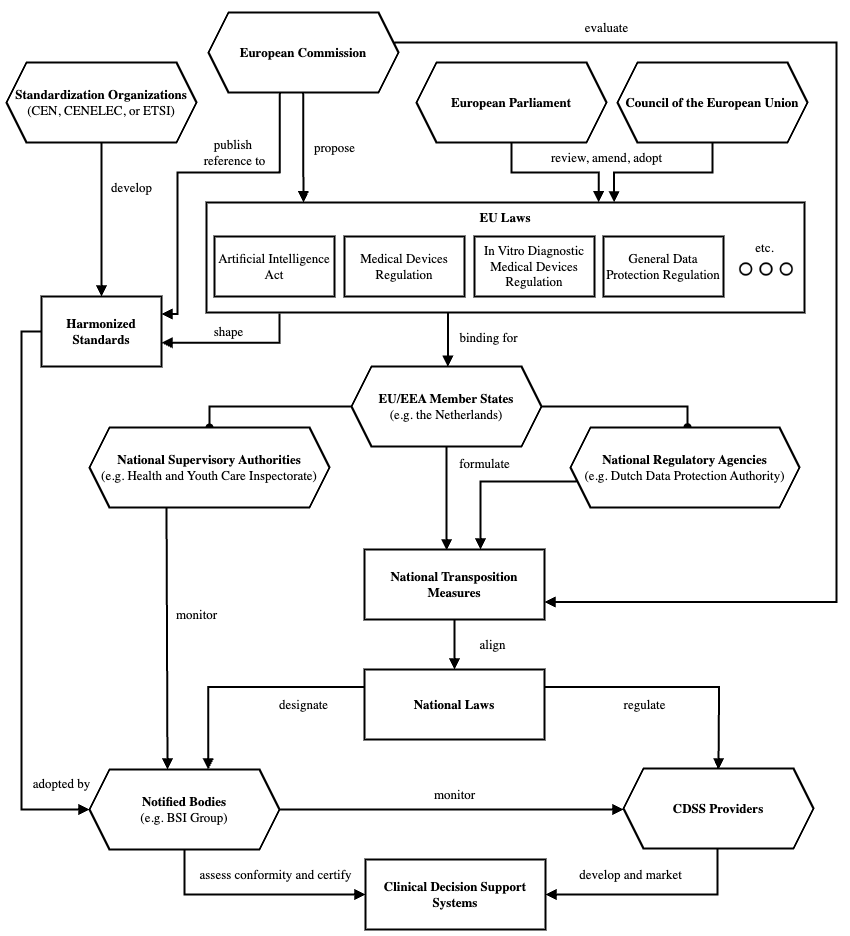

Recently I mapped the governance structure for decision support systems operating in the European single market. The diagram which I derived is by no means comprehensive nor complete, but it can nonetheless serve as an on-ramp for the unitiated. A brief explanation follows.

First and foremost, a ’clinical decision support system’ (CDSS) is a biomedical term which does not constitute a distinct legal category in the European Union law. From the legislative perspective, CDSSs are encompassed within several legal categories such as medical devices and high-risk AI systems. The European Commission proposes legislation, some of which affects CDSS development, operations, and marketing. Examples of such legislation include the EU AI Act, the Medical Devices Regulation (MDR), the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR), and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Once proposed, legislative acts have to be reviewed, amended, and approved by the by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. When the adopted legislation is binding for member states, national governments are obliged to align their national laws with the EU laws. They do this through the formulation of national transposition measures which they subsequently submit to the European Commission for evaluation. Typically, the formulation of transposition measures involves input from national regulatory agencies and possibly other stakeholders.

As an example, the EU has recently adopted the AI Act which obliges the Netherlands, as a member state, to align their national laws to the requirements set in the Act. Two national regulatory agencies, the Dutch Data Protection Authority (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens and the Dutch Authority for Digital Infrastructure (Rijksinspectie Digitale Infrastructuur) have formulated advice for Dutch ministries concerning the supervisory structure for the AI Act. One of the recommendations is that the supervision of AI in different sectors remains with the existing national supervisory authorities. For the healthcare sector, this would be the Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (Inspectie Gezondheidzorg en Jeugd). National transposition measures for the AI Act are still being negotiated in the Netherlands.

From the perspective of CDSS providers and manufacturers, CDSSs have to demonstrate conformance to the national and EU laws in order to be placed on the European Single Market. Often, the easiest way to demonstrate conformance is via certification. For this, CDSS providers can reach out to notified bodies, companies which are designated by member states to assess product conformity and provide certification. In the Netherlands, this is currently done by one of the four notified bodies. As the national supervisory authority for healthcare, the Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate oversees the work of notified bodies, which in turn assess and certify individual CDSSs. If Dutch ministries back the aforementioned advice and implement such transposition measures, the obligations of notified bodies and the supervisory authority would expand to encompass the new requirements set forth by the EU AI Act.

From the perspective of notified bodies, the EU and national laws tend to be ambiguous. Legal language is subject to later legal interpretation. This means that there is a gap between the legal objectives and their technical operationalizations. In the European Single Market, this gap is often bridged via harmonized standards. These documents, formulated by standardization organizations, specify the minimum consensus regarding the acceptable technical methods to demonstrate conformance of a product. Notified bodies use harmonized standards to assess and certify CDSSs. Interestingly, it is not mandatory in the EU nor in the US for a product to comply with harmonized standards. Instead, harmonized standards serve as a heuristic for system providers and lawyers who would otherwise have to demonstrate system compliance in a more tedious way. A downside of harmonized standards, however, is that they are often in line with the minimum technical consensus that typically falls short of the scientific state-of-the-art. Once a harmonized standard is formulated, the European Commission publishes a reference to this standard in the Official Journal of the European Union. Harmonized standards enable standardized functioning of systems operating within the European Single Market.

Got questions or comments? Reach out!